1930-48: Childhood

Robert Arneson is born on September 4, 1930, in Benicia, CA, the younger of two sons. As a child he struggles with a congenital hearing impairment, which went undiagnosed for decades. Not until he is in his thirties does he finally begin using hearing aids, however poor hearing would affect his work and relationships for his entire life; two of his sons also inherit his hearing impairment.

Arneson’s brother Vernon, while serving in the Air Force as a B-17 Bomber pilot, is shot down over Germany in 1944 and held as a prisoner of war for over a year. The experience leaves him traumatized and later informs Arneson’s own anti-war work.

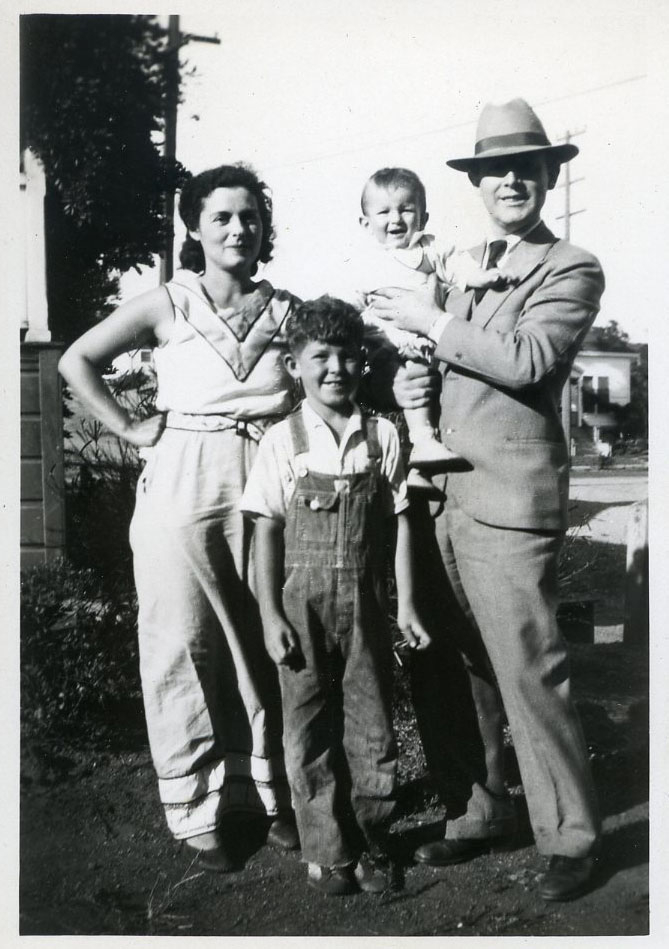

Family portrait of Helena, Vernon, Robert, and Arthur Arneson at 402 West J Street in Benicia, CA, 1931.

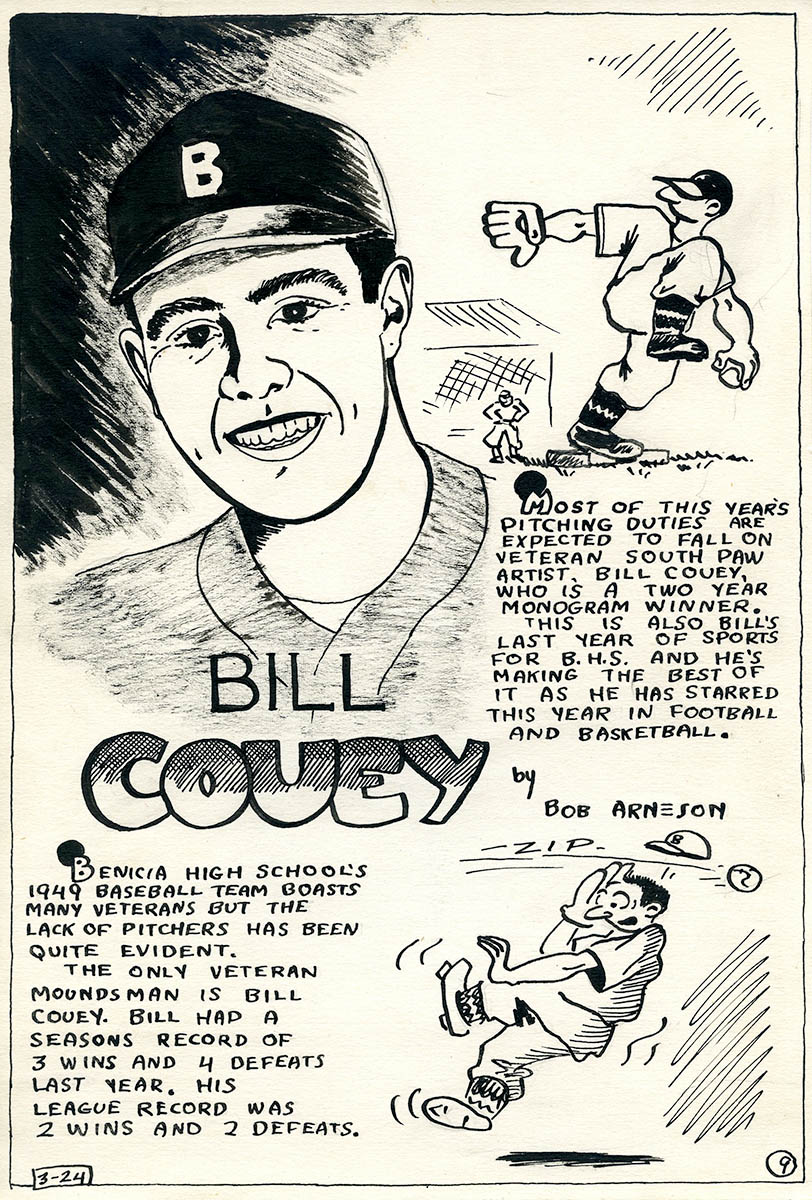

Encouraged by his father, who was a skilled draftsman, Arneson begins drawing at a young age. His skill eventually leads him to create his own comics while still in high school, featuring a football star who would heroically save the game – and the day. Arneson himself plays quarterback for his high school football team, but by his own admission, was not as good as his alter-ego. His cartooning skills lead to a job drawing caricatures of sports stars for the local paper, the Benicia Herald.

Baseball comic featured in the Benicia Herald, 1949.

1949-56: Education

Graduates from high school and enrolls in the College of Marin, where he continues to play football until a knee injury ends his athletic career. He continues to draw for the Herald however, inspiring him to pursue a career in cartooning.

Enrolls in the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1952 on a partial scholarship but takes time off after deciding against a future in cartoons, instead working at the Shell Oil refinery for most of the year. Arneson returns to CCAC in 1953, this time pursuing a degree in art education. Through a roommate he is exposed to a new and liberal view point, from sources like The New Republic, The Nation and the local KPFA radio station, in contrast to his conservative upbringing.

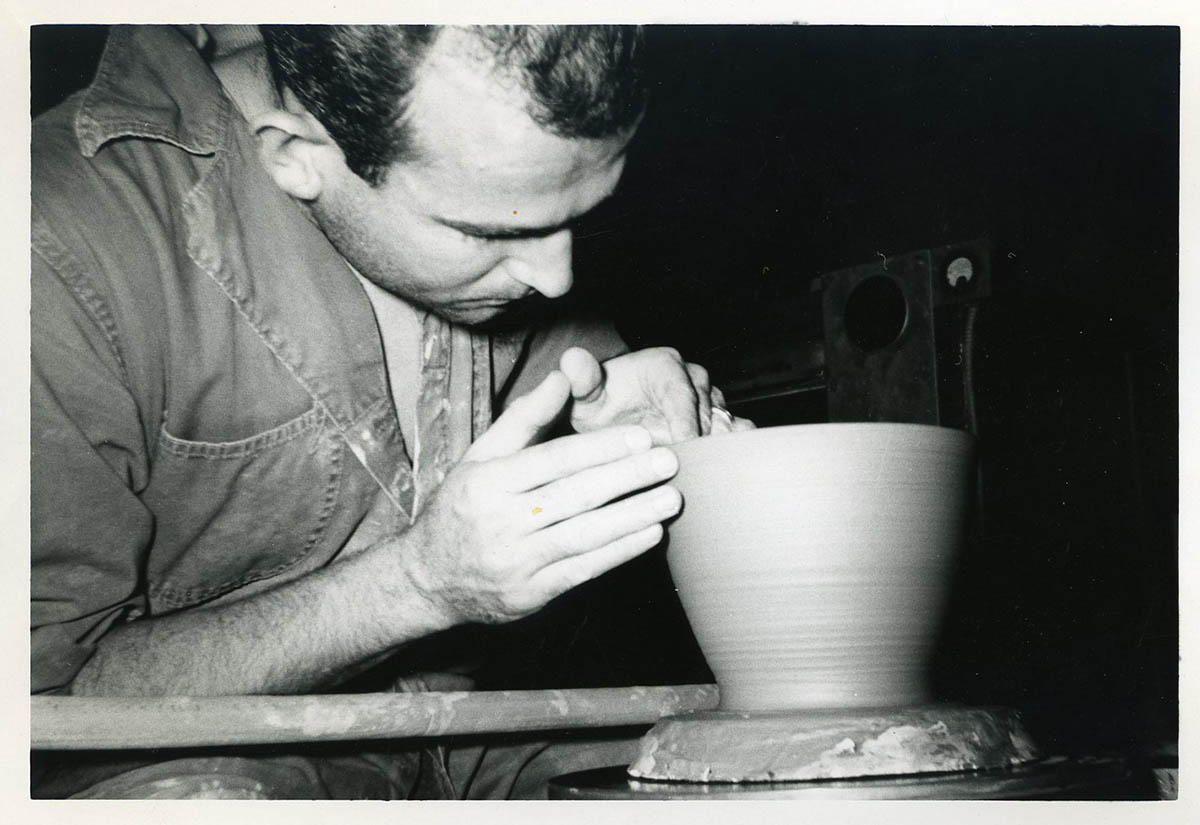

Arneson on the wheel at Menlo-Atherton High School, Benicia, CA, 1956.

In 1954, he graduates CCAC with distinction, though struggled in ceramics courses and takes a summer class in hopes of improving. That fall he takes a position teaching art at Menlo-Atherton High School, including ceramics – a responsibility that further galvanizes him to develop his skills.

Marries Jeanette Jensen in 1955, their first son Leif is born the following year. Their honeymoon trip to Mexico furthers his interest in ceramics and art, leading him to take courses with Herbert Saunders at San Jose Sate and Edith Heath at CCAC over the summer of 1956.

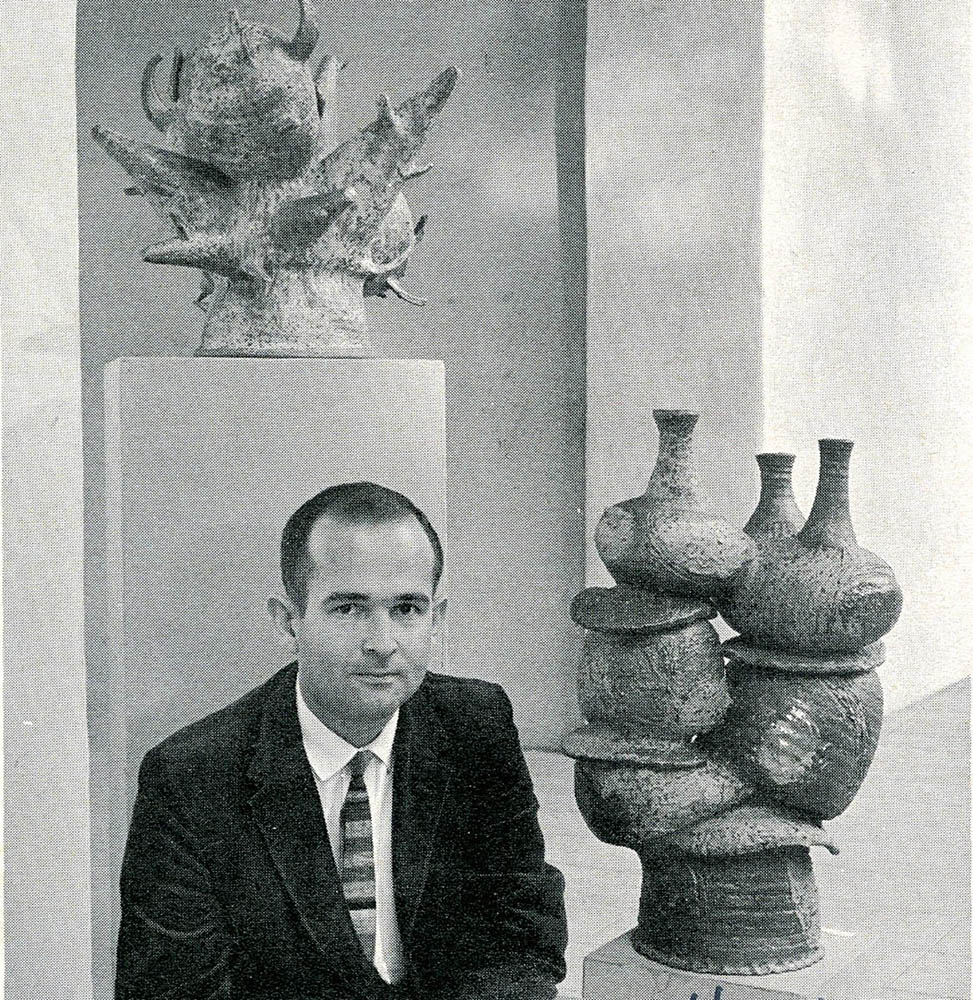

Mills College MFA Masters Project, Oakland, CA, 1958.

1957-61: Mills College

Leaves his position at Menlo-Atherton to pursue an MFA at Mills College, studying under Tony Prieto. As part of the Mills ceramics department, Arneson begins demonstrating wheel throwing annually at the California State Fair, where he would also show his pottery. It is at the fair that he first comes to know the work of Peter Voulkos, a huge influence in his shift to non-traditional ceramic sculpture.

Graduates from Mills with MFA in 1958 and takes a teaching position at Santa Rosa Junior College that fall. There he meets fellow sculptors Steve Kaltenbach and Ed Higgins. Takes a teaching position at Fremont High School, Oakland in 1959 and joins the Mills College Ceramics Guild for access to studio space; soon after, his son Kreg is born. Voulkos begins teaching at UC Berkeley, giving Arneson an opportunity to meet him and his students, which pushes his work further towards sculptural forms. Arneson’s first solo exhibition, at the Oakland Museum, is held the following year.

Arneson in Mills College studio with Sign Post, Oakland, CA, 1961.

Joins faculty at Mills College in 1960, teaching ‘design and crafts’ however Arneson’s concept of ceramics as sculpture is at odds with his colleagues. His son Derek is born at the beginning of 1961. At the State Fair that summer, Arneson makes No Deposit, No Return – a ceramic bottle that would be his first ‘pop’ object.

Arneson at Oakland Museum exhibition, Oakland, CA, 1960.

1962-66: Davis

Richard Nelson hires Arneson as an assistant professor at University of California, Davis, to build a ceramics program in the newly-created art department. His new colleagues include Roy De Forest, Wayne Thiebaud, William T. Wiley, Tio Giambruni and Manuel Neri. Arneson sets up the new studio in Temporary Building 9 (TB-9), where he would continue to teach and create work over his decades at Davis. To be closer to his job, the family moves to a tract house at 1303 Alice Street in Davis.

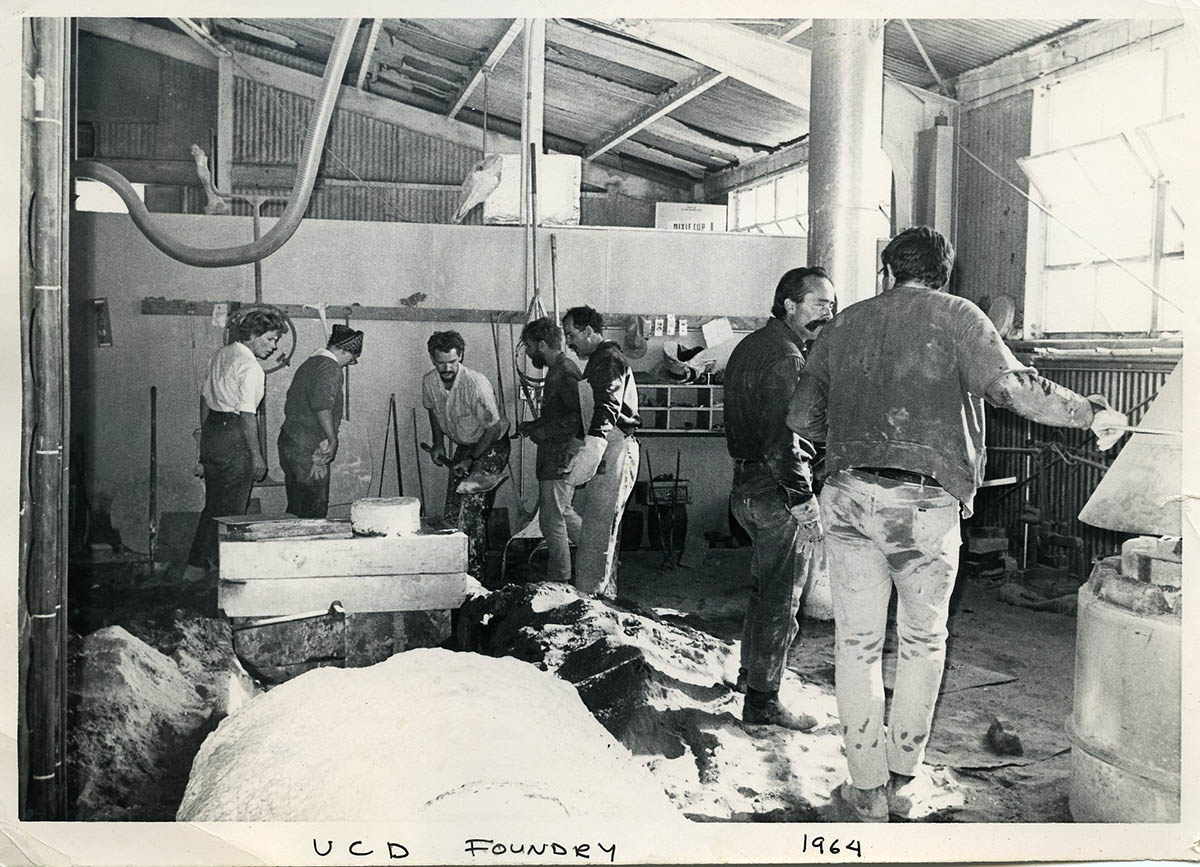

Ruth Horsting, Mary Stewart, Ed Higgins, Peter Vandenberge, Robert Arneson, Tio Giambruni, David Gilhooly in TB-9 Foundry, Davis, CA, 1964.

In 1963, Arneson is invited to show in California Sculpture at the Kaiser Center Roof Garden in Oakland. His submission, Funk John, so horrifies an executive that it is ordered removed from the exhibition. This was the emergence of figurative elements in Arneson’s work – and the first of his ‘funk’ sculptures which grew to include not only toilets, but trophies and other grotesquely modified objects. In 1963, Tio Giambruni constructs a foundry in TB-9 following Voulkos’s example at Berkeley; faculty and students at Davis, including Arneson, begin experimenting with bronze and aluminum casting. That year Arneson meets Adeliza McHugh, owner of the Candy Store Gallery in Folsom, CA, whom he would go on to show with for many years.

Funk John, 1965, glazed stoneware, ceramic, 36 x 28 x 20 inches. Destroyed.

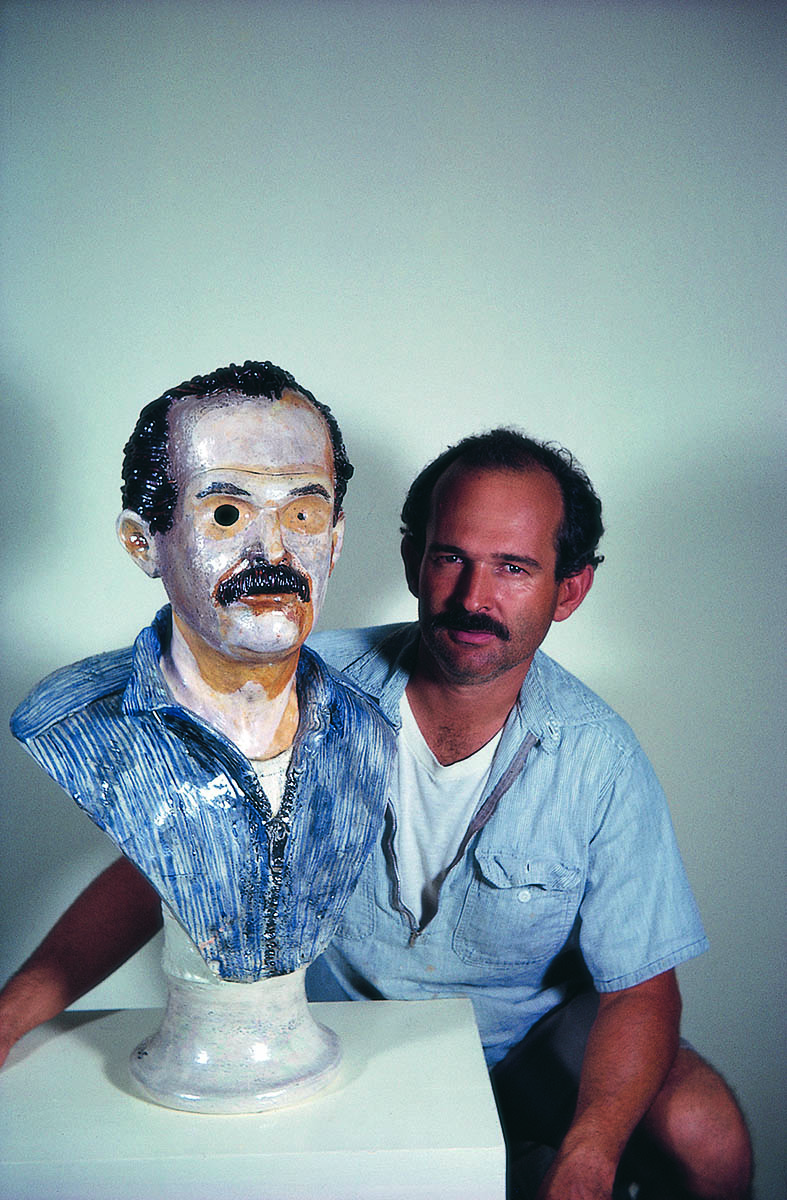

Arneson’s youngest son Kirk is born at the beginning of 1964. That spring, Arneson travels to New York for the World Craft Council, in what would become the first of yearly visits. On this trip he meets the dealer Allan Stone, who exhibits Arneson’s ceramics at his New York gallery, later that year, including some of the “toilet” pieces.” In what he later describes as an attempt to make “serious” work, Arneson completes his first self-portrait bust, Portrait of the Artist Losing His Marbles in 1965. His shift in subject matter coincides with his adoption of low-fire techniques, expanding his palette and range of painterly glazing techniques.

Arneson with Self-Portrait of the Artist Losing His Marbles, before crack, 1965.

Arneson’s new approach is brought to bear in sculptures such as Typewriter (1966) and the extended series of Alice House works he begins around this time, taking as their subject his house on Alice Street. He later organizes a weekend exhibition of works from the series, including sculptures and drawings, in the living room of the eponymous house.

Arneson at 1303 Alice Street, Davis, CA, 1967.

1967-71: ‘Funk’

Arneson begins showing with Hansen Gallery, soon to be Hansen Fuller Gallery in San Francisco in 1967; that year he is also included in the survey, Young California Artists at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Peter Selz’s era-defining Funk show opens at the UC Berkeley Museum, Typewriter is included.

An Institute of Creative Arts grant allows Arneson to take a sabbatical from teaching for the ’67-’68 academic year; Clayton Bailey covers his courses at Davis. While on sabbatical, Arneson spends most of the year in New York, where he is introduced by artist William T Wiley to the dealer Allan Frumkin and the artist H. C. Westermann. Without access to facilities in New York, Arneson focuses on paintings and drawings; Typewriter is included in the MoMA exhibition, Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage. He teaches for the summer at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Earth Color, 1968, magna paint on canvas, 24 x 30 inches.

Building on his vernacular of ‘Funk’ objects, Arneson begins constructing teapots, which leads to a collaboration with Roy De Forest in 1969 on series of ceramics they call Bob and Roy Ware. The series is exhibited at Esther Robles Gallery, Los Angeles and the Candy Store Gallery the following year. Arneson is included in the Smithsonian Institute’s national touring exhibition, Objects: USA; he also shows recent ceramics in solo exhibitions at Hansen Fuller Gallery, SF and Allan Stone Gallery, NY. In the fall of 1969, he travels to Europe for the first time.

Over the following year, Arneson experiments with assemblages from small, slip-cast porcelain parts. Arneson is included in the Whitney Museum’s 1970 Sculpture Annual, where a group of ‘sinking brick’ plates are shown.

Life in East Potts, 1969, underglazed and glazed earthenware, 12 inches high.

He again takes a sabbatical from Davis for the ’70-’71 academic year, this time moving back to Benicia where he works out of a small studio space in an old waterfront warehouse. He returns to self-portraiture for the first time since 1965 with The Cook, A Self-Portrait later re-titled, Smorgi-Bob. The sculpture is shown later that year in New York, at the Museum of Contemporary Craft’s exhibition, Clayworks: 20 Americans. Partly inspired by Smorgi-Bob, Arneson begins a series of trompe l’oiel sculptures, Dirty Dishes, that are shown at Hansen Fuller in 1971.

Arneson with Smorgi-Bob, The Chef, 1971.

1972-76: The Breakthrough

Following Smorgi-Bob, Arneson begins a series of self-portraits including Hollow Jesture, a pivotal, life-sized portrait, also made in the small Benicia studio, which he maintained until 1973. This group of busts is shown in My Head in Ceramics at Hansen Fuller Gallery, in 1972. The exhibition is a sell-out success and Arneson continues to focus on portrait busts for the next several years, building molds of his head at various scales to facilitate the process. The gallery at California State University, Hayward organizes the exhibition Nut Art in 1972, which brings together an eccentric group of artists all working between the North Bay and Sacramento area. Arneson is included, along with friends and artists De Forest, Bailey, David Gilhooly (a former student), Maija Peeples-Bright, and others; the title is an informal moniker the group created to define their off-beat styles and subjects.

Arneson and Jeanette separate in 1971, eventually divorcing at the end of 1972 while sharing custody of their four sons. Arneson and the artist Sandra Shannonhouse are married in the spring of 1973. That same year he is promoted to full professor at Davis.

Arneson next to A Hollow Jesture at his 146 West E St. studio in Benicia, CA, 1971.

Besides his portraits and self-portraits, which steadily become more ambitious and conceptually complex, Arneson completes a number of monumental floor pieces between 1973 and 1980, beginning with Current Event (1973), and the culmination of his Alice House series, The Palace at 9am (1974).

His first museum retrospective is organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 1974, it travels to SFMOMA. That spring, Arneson and Shannonhouse visit the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico; the dealer Allan Frumkin includes Arneson in a group exhibition of California Ceramics at his New York gallery. Frumkin formally begins representing Arneson the following year, in 1975, with a solo exhibition in New York of recent ceramic sculpture including five major floor works. Shortly before the exhibition opens, Arneson is diagnosed with bladder cancer and undergoes emergency surgery. While the surgery was a success, he received further treatment the following year and the disease would continue to plague him for the rest of his life.

Arneson at My Head in Ceramics, Hansen Fuller Gallery, San Francisco, CA, 1972.

Arneson and Shannonhouse purchase a property at the corner of East E and First Streets in Benicia with the intent to renovate it as a home for the family and a studio for them both. They finally move from Alice Street to Benicia in the summer of 1976.

That year, with the support of a NEA grant, Roger Hankins begins working for Arneson as a studio assistant and helps with the set up of the new Benicia studio, including the installation of a large gas kiln in 1977. Through Frumkin, Arneson begins working with Jack Lemon of Landfall Press to publish lithographs – together they produce more than a dozen prints over more than ten years.

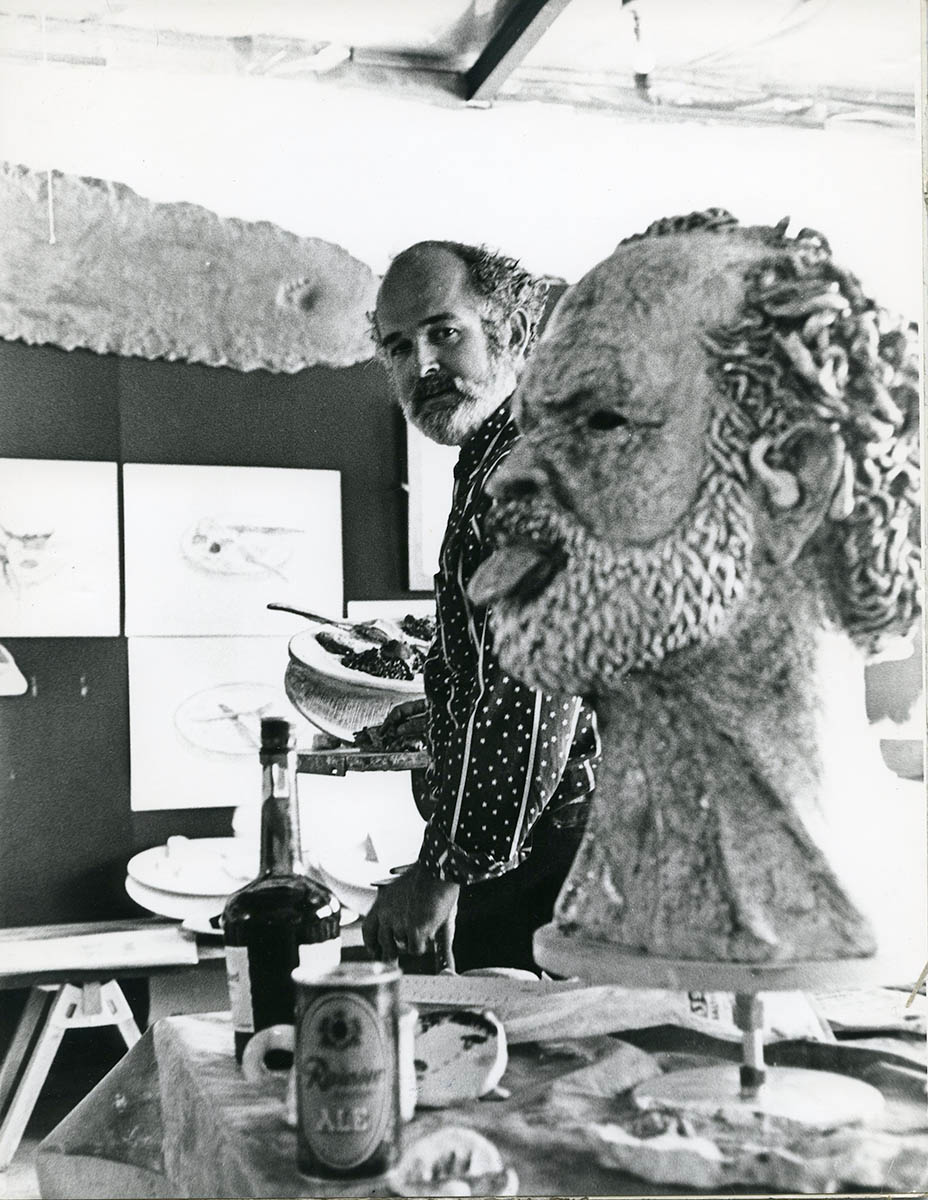

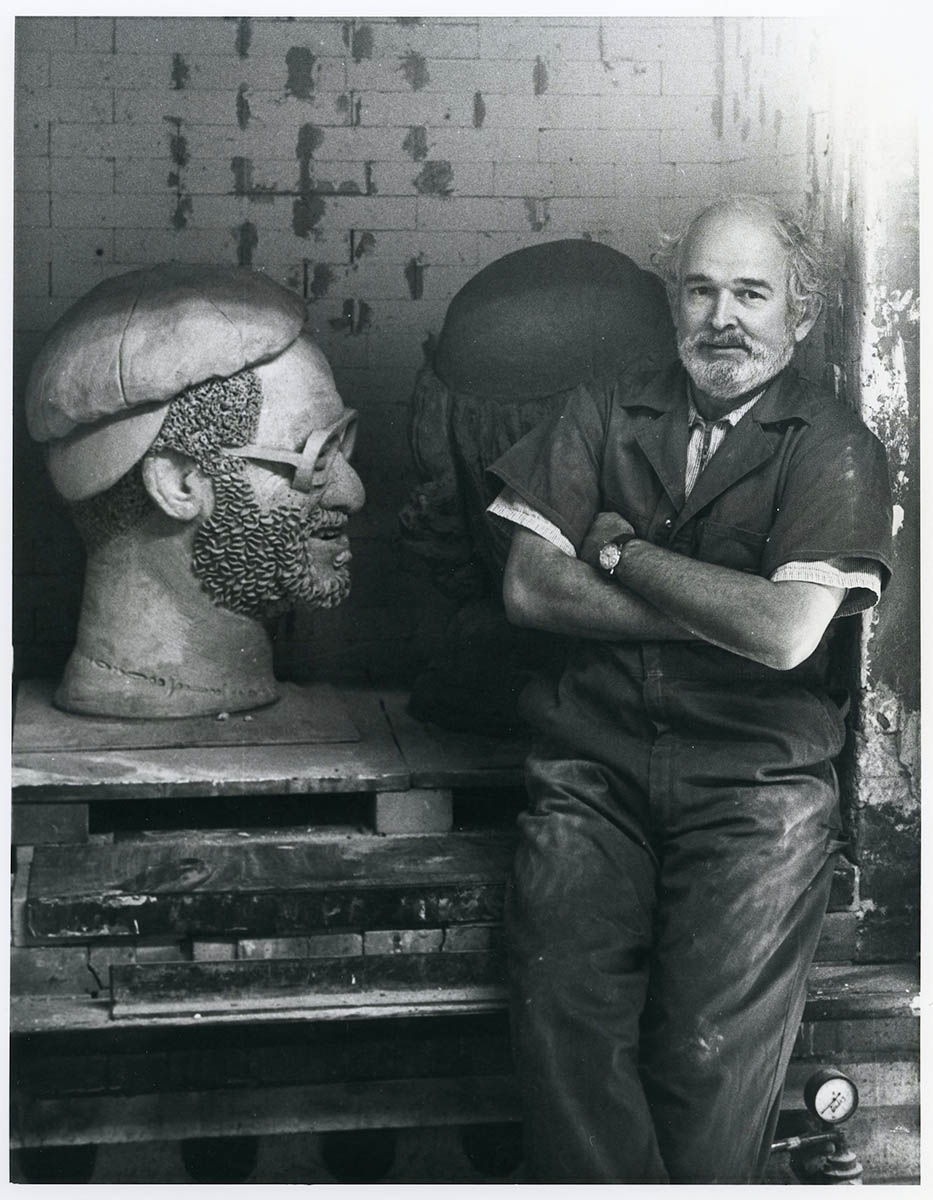

Arneson sculpting General Best, Benicia, CA, 1977.

1977-80: International Recognition

Solo exhibitions at Allan Frumkin and Hansen Fuller in 1977 feature, respectively, new portrait busts and water-themed floor works. In the summer of 1978, Arneson and Shannonhouse visit Europe, making stops at many museums, including to see the Grunewald Altar in Colmar. Despite a lengthy recovery from further complications of his cancer, Arneson completes several new major portraits and self-portraits in 1978, which are shown the following year in Heroes and Clowns at the Allan Frumkin Gallery, New York. Captain Ace and Splat (both 1978) are shown in the Whitney Biennial in 1979 and Moore College of Art in Philadelphia organizes an exhibition of self-portraits. West Coast Ceramics opens at the Stedelijk Museum of Art, which includes their recent acquisition, Captain Ace; Arneson attends the opening.

Arneson with Mike and David in the TB-9 kiln, Davis, CA, 1977.

George Grant takes over from Roger Hankins as Arneson’s studio assistant in 1979, and plays a key role in the fabrication of the monumental Ikaros, which is completed in 1980. That summer Arneson and his family travel to London and Greece, where the ancient statuary they see proves to be hugely influential. Arneson is introduced to Mark Anderson of Walla Walla Foundry in 1980 – he begins casting with the foundry in 1980 and they continue to collaborate on more than 80 bronzes up until Arneson’s death.

Left to right: You Don’t Belong Here, 1981, bronze, unique, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Collection of the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum. Massetered, 1981, bronze, unique with ceramic pedestal, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Collection of the Oakland Museum of California. Sharp Focused, 1981, bronze, unique with ceramic pedestal, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Heading Home, 1981, bronze, unique with ceramic pedestal, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Pour Walla, 1981, bronze, unique with ceramic pedestal, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Head Fold, 1981, bronze, unique with ceramic pedestal, 18 x 11 x 12 inches. Photo: M. Lee Fatherree.

1981-86: Politics

In early 1981, Arneson is commissioned to make a portrait of George Moscone, the former mayor of San Francisco who, with Harvey Milk, was assassinated by Dan White in 1978. The sculpture is intended to grace a newly-constructed convention center to be named after Moscone. However, ahead of the dedication ceremony, the pedestal base Arneson created, inscribed with multiple references to Moscone’s life, the assassination and the controversial trial that followed it, is deemed too incendiary to display. The controversy that ensues takes Arneson by surprise, but when asked to replace the base, he refuses, ultimately withdrawing the piece and relinquishing the commission.

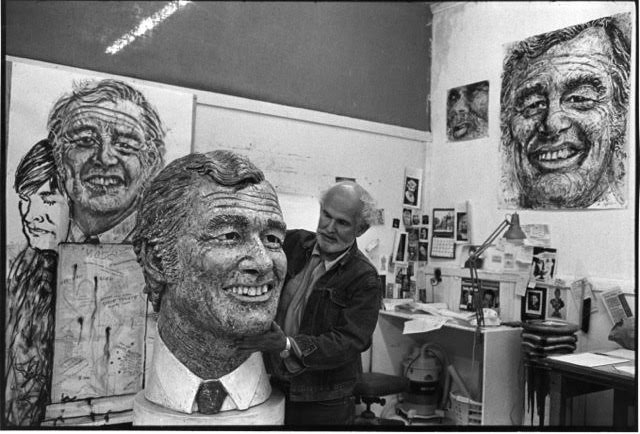

Arneson with Portrait of George, 1981. Photo: Ira Nowinski.

The Whitney Museum of American Art opens the landmark exhibition Ceramic Sculpture: Six Artists later that year, featuring Arneson alongside his California contemporaries Voulkos, Shaw, Gilhooly, Ken Price and John Mason. In his review of the exhibition for The New York Times, Hilton Kramer lambasts Arneson in particular, calling out “the celebration of kitsch, low taste, visual gags, facetious narrative and a certain vein of sophomoric humor… a spirit best defined as defiant provincialism.” Coming on the heels of the Moscone incident, the review is a major blow to Arneson and inspires his rebuttal through sculptures like the monumental California Artist that he completes in 1982.

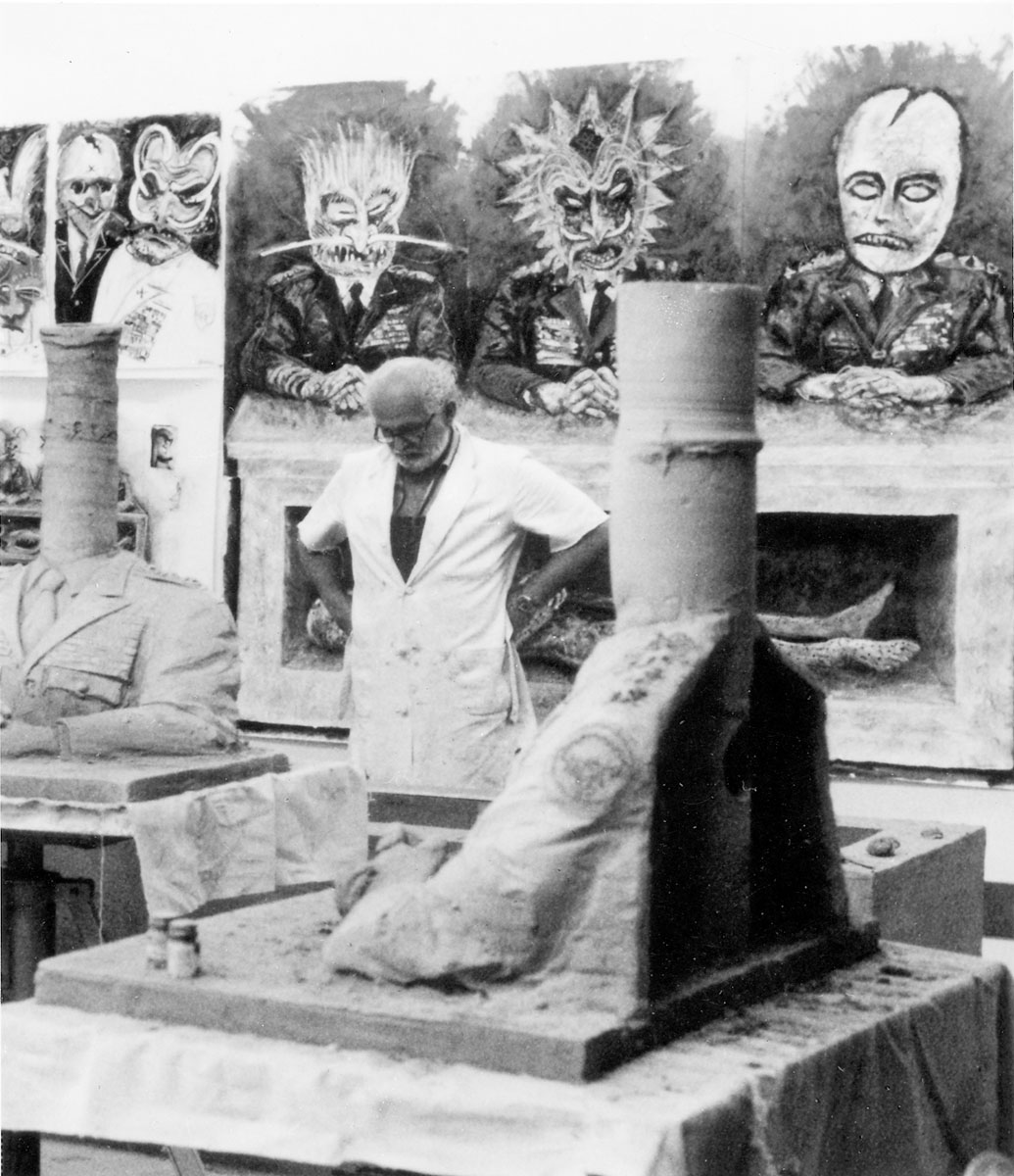

While Arneson’s work had been openly confrontational since he made the first toilet, and though he was politically engaged in his personal life, it was not until 1981 that his work became overtly political. In 1982, he begins his most ambitious series to date, on the subject of nuclear war and the threat of proliferation. Arneson had recently completed his new Benicia studio, which had a separate loft space he could use to draw in. Going forward, large-scale, detailed works on paper increasingly become an important part of his process, in tandem with his work in clay.

California Artist, 1982, glazed ceramic, 77 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 25 inches. Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Photo: M. Lee Fatherree.

The Crocker Museum in Sacramento organizes the first survey of his drawings in 1983. The anti-nuclear series is first shown in New York, at Allan Frumkin Gallery in 1983; Arneson is also included in the exhibition Controversial Public Art at the Madison Art Museum that same year.

Between 1982-1984, Arneson undergoes a string of surgeries in an attempt to find a permanent treatment for his cancer; ultimately his bladder is removed, then reconstructed, in what his doctors believe is a successful procedure.

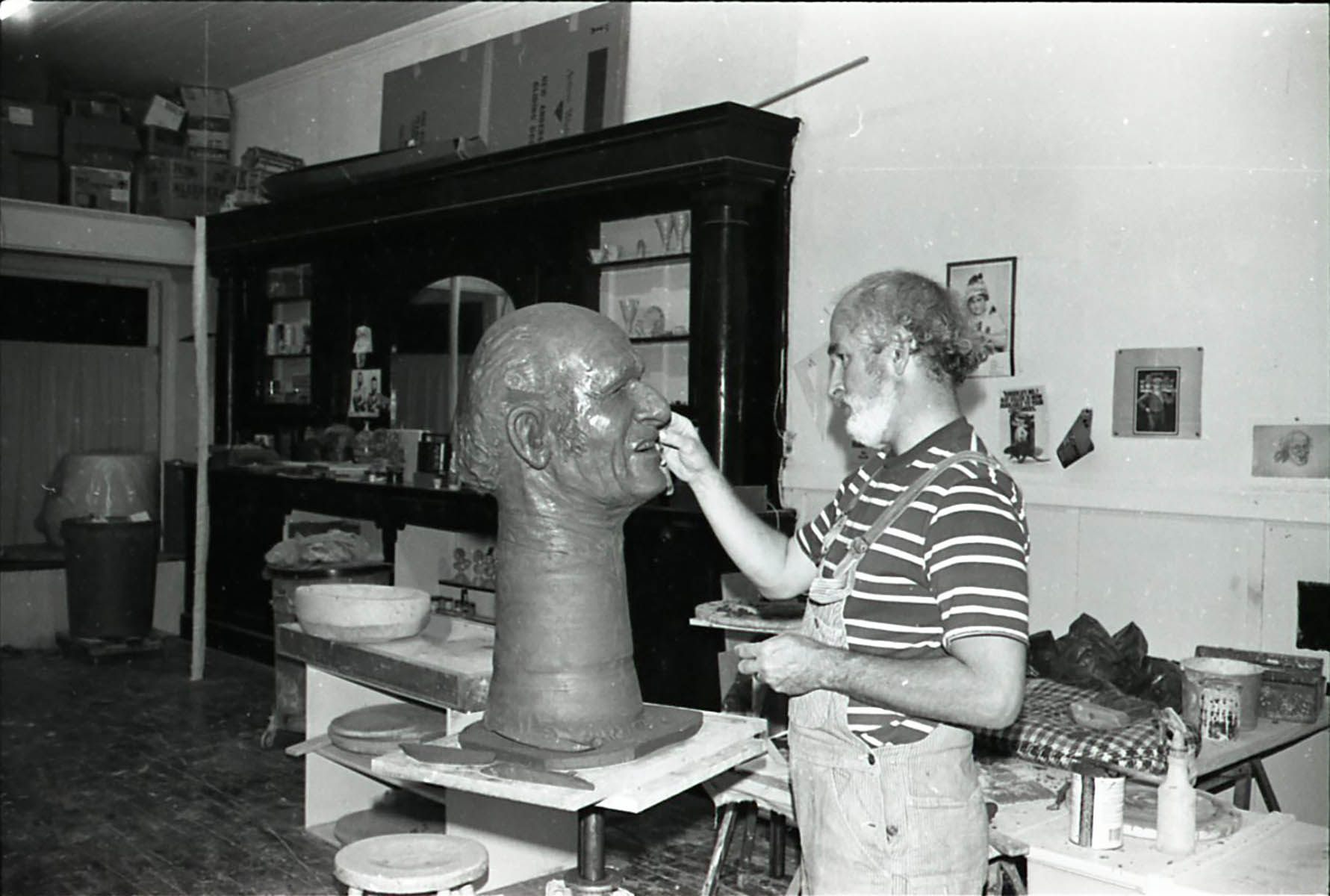

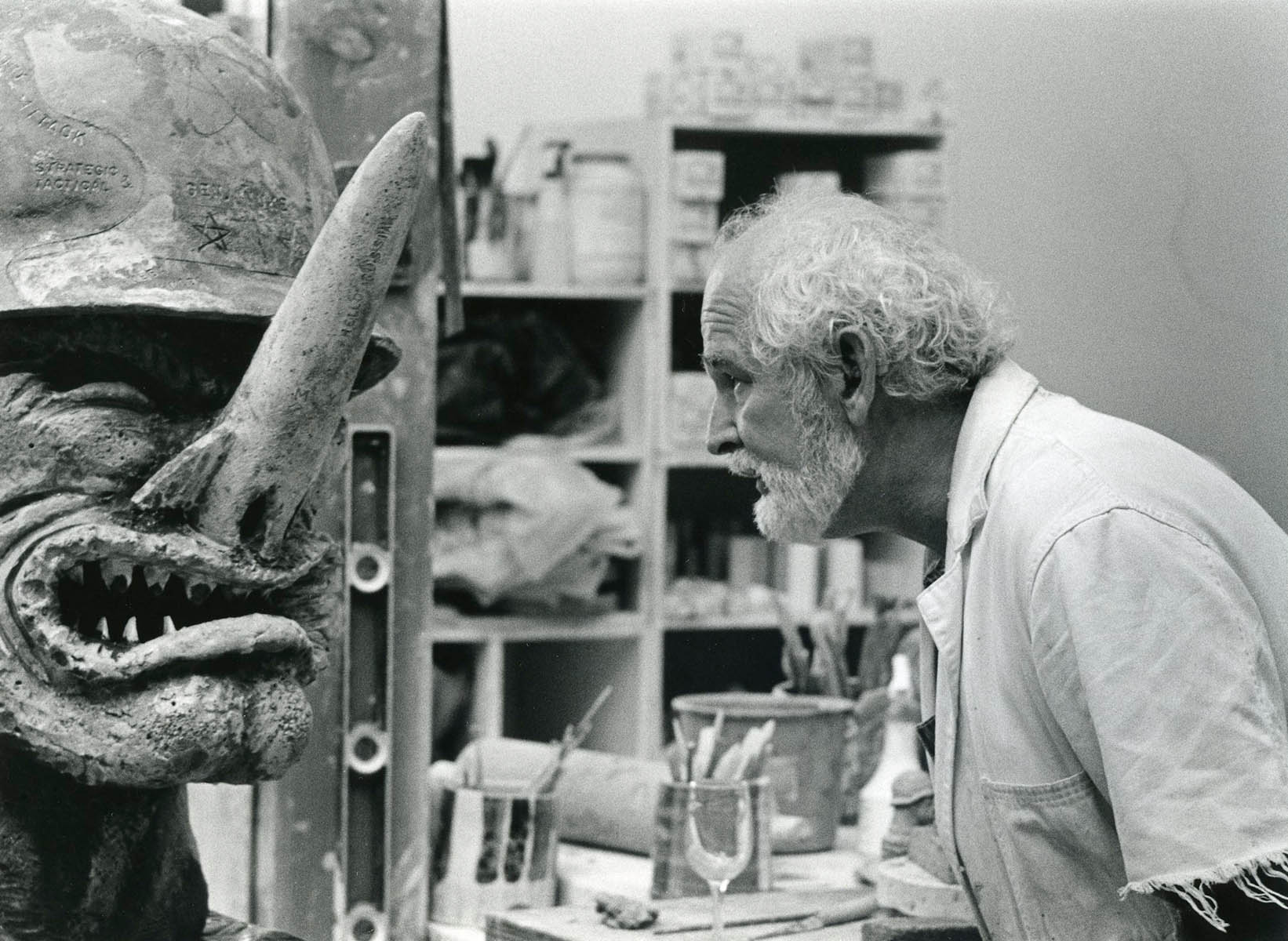

Arneson in studio with General Nuke, 1984. Photo: Hedi B. Desuyo.

Arneson completes the monumental anti-war sculpture Sarcophagus in 1984, inspired in part by the Grunewald Altar. The anti-nuclear works continue to occupy Arneson’s attention through 1986, however he begins to expand his political focus with a series of caricatures of Ronald Reagan. The Des Moines Art Center organizes a major retrospective of Arneson’s work in 1986, the exhibition travels to the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the Portland Art Museum and the Oakland Museum of California. His daughter with Shannonhouse, Tenaya, is born that same year.

Arneson in studio with Sarcophagus, 1984. Photo: Hedi B. Desuyo.

1987-92: Pollock and Mortality

While politics continue to be of interest to Arneson, by 1987 Jackson Pollock becomes a primary focus of his work. Arneson had started to explore the late artist as a subject in 1982, fascinated by the myth of personality and his tragic death. He makes several portraits and self-portraits in an investigation of Pollock’s psyche.

In the fall of 1987, artist Mike Henderson, a fellow faculty member at Davis, files an accusation of racism against Arneson, on the basis of some remarks. Arneson is deeply shaken by the incident, and though the matter is resolved, it prompts him to begin a series of portraits of Black men the following year. Most of 1988 is given over to the construction of Guardians of the Secret II, a monumental sculptural envisioning of Pollock’s painting of the same name. Arneson’s mother Helena dies that same year.

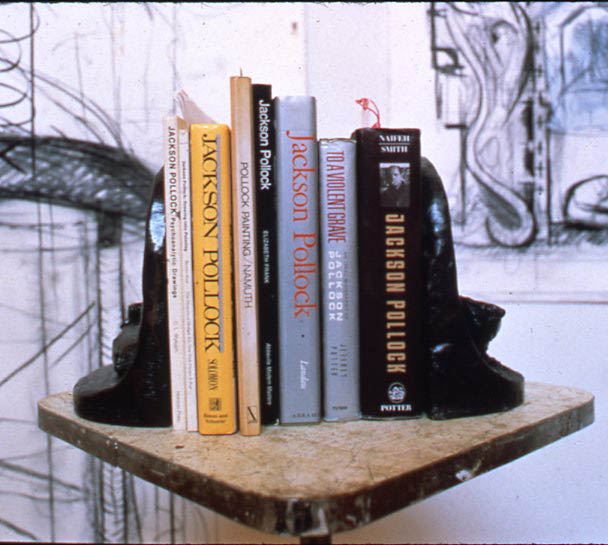

Books about Pollock being held by Saga of Jackson Pollock Bookends, 1990. Photo: James Woodson.

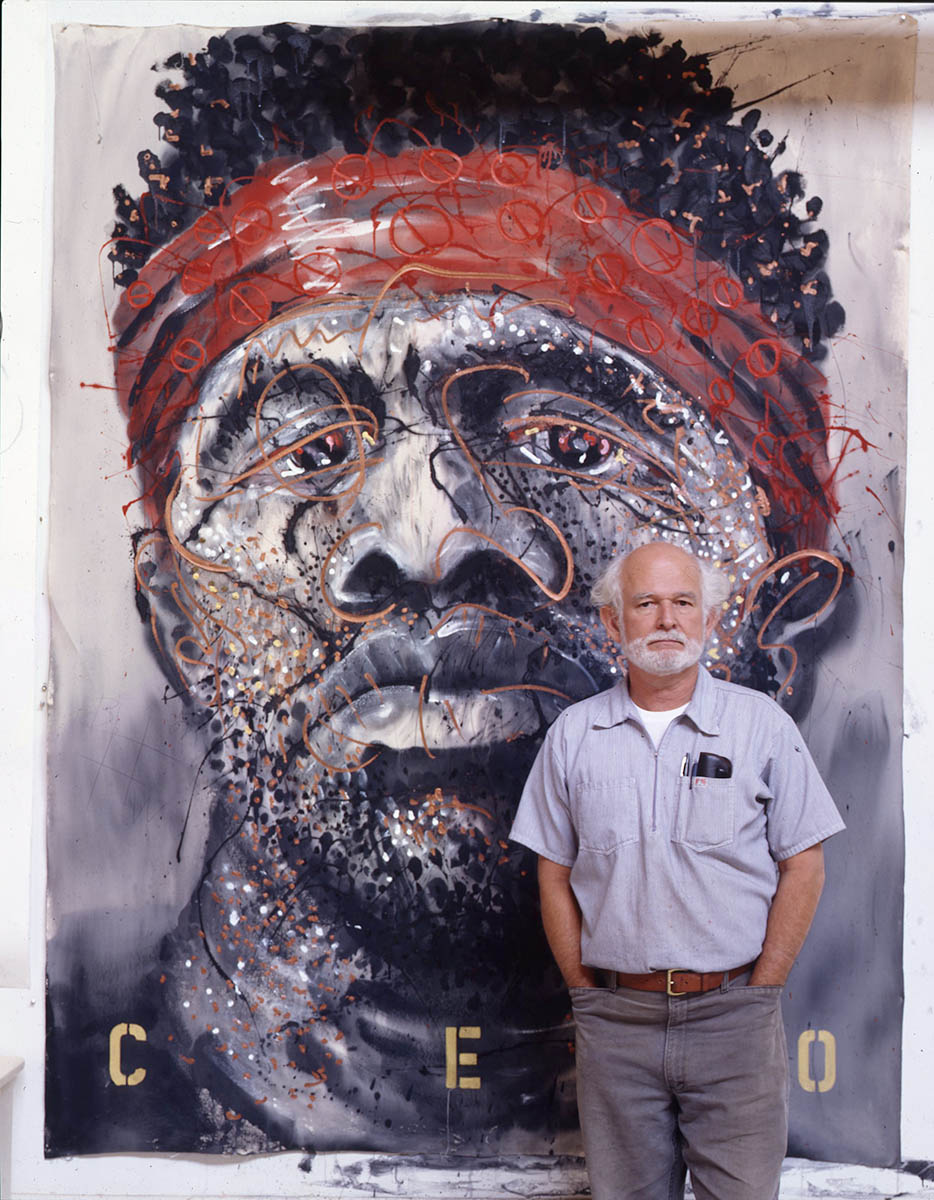

Arneson expands on the Blacks series in 1989, most of the drawings and sculptures are based on photographic material he gathers from magazines, some of musicians, but also from a Time Magazine feature in July 1989 on victims of gun violence in America. The series is exhibited at Frumkin/Adams Gallery in New York in 1990 – the press release includes Arneson’s statement: “My recent images of Black Americans in black and white about white and black, are hard looking – looking hard – confronting our perceptual awareness and attitudes toward the national dilemma, racism.”

Arneson with C.E.O., 1990. Photo: James Woodson.

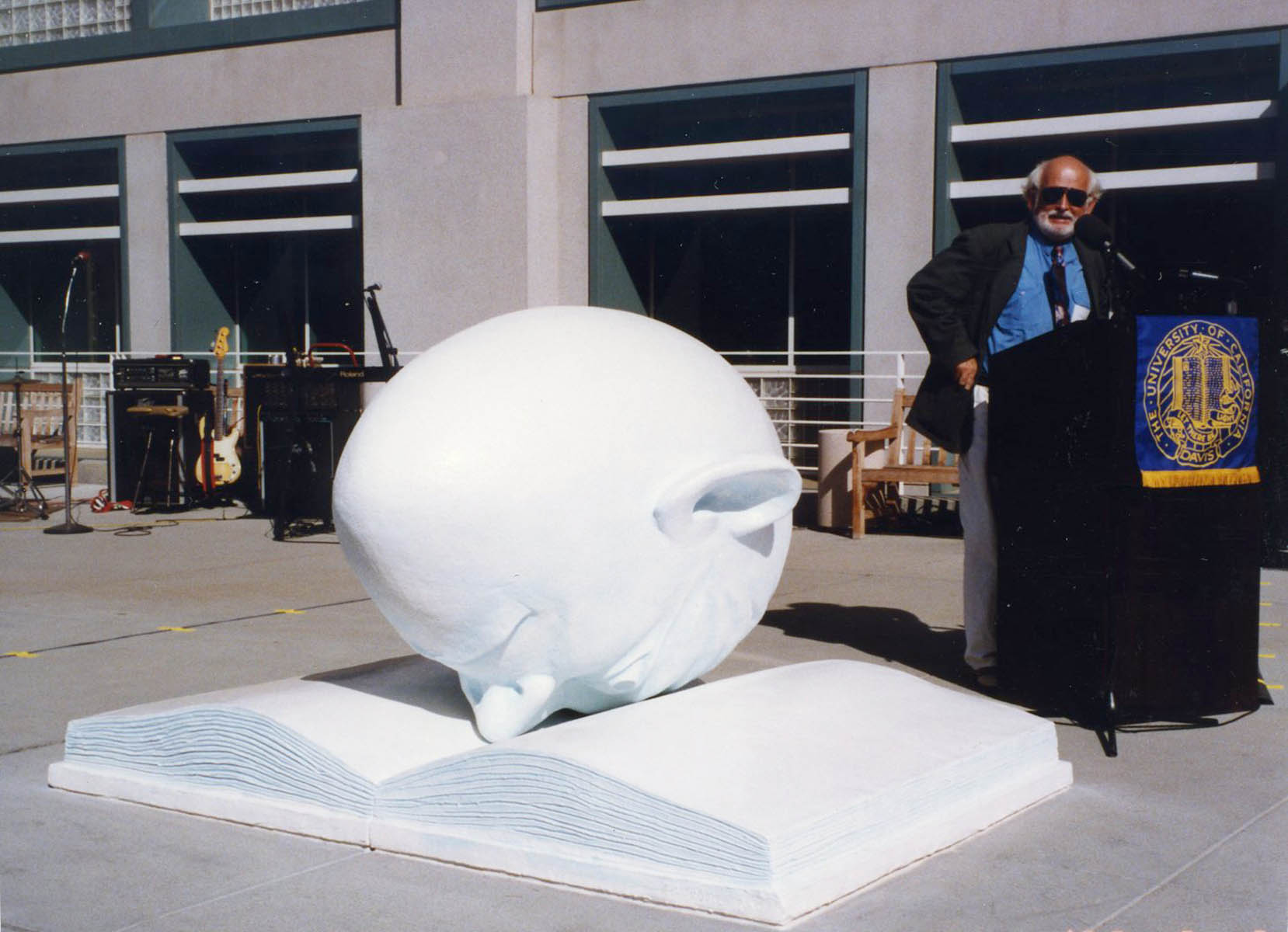

At the end of the 1991 academic year, Arneson formally retires from teaching. He begins a number of large bronzes at Walla Walla, many referencing Classical Greek statuary, including the Egg Heads for the UC Davis campus and Benicia Bench, which is installed on the Benicia waterfront a short distance from his childhood home. That summer he visits the Pollock-Krasner House in East Hampton, New York. Work from the Pollock series is exhibited at the House in 1992, while Guardians of the Secret II is shown for the first time at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia that same year.

Arneson with Bookhead at UC Davis, Davis, CA, 1991. Photo: Sandra Shannonhouse.

In the fall of 1991, Arneson discovers his cancer has returned – and spread. He undergoes further surgery and chemotherapy in early 1992, during which he makes the sculptures Chemo I and Chemo II. He continues to produce new work through 1992, including a number of ceramic double portraits, drawings and further bronzes. Arneson learns the treatment is unsuccessful in September 1992; his last work, the ceramic Self-Portrait at 62 is completed shortly after and posthumously cast in bronze. Arneson dies at home in Benicia, on November 2, 1992.